Introduction

This page is for those of you who zipped through the other materials this week.

Spatial archaeology looks at the patterning of the remains of human activity in (usually geographic) space over time. It can encompass working with geographic information systems, and it can encompass web mapping (on which see ODATE 3.5). A geographic information system is a way of stacking a series of maps of the same region that contain different kinds of information. Perhaps one layer is a map of soils. Another might be information on slope (steepness) or aspect (direction the slope faces). Another layer might have information on the relative fertility of the soil. To this stack we might add distribution maps of human activity for a given period (perhaps scatters of pottery). The power of GIS lies in its ability to query the ways these different layers might intersect. How does human activity 3000 years ago in the area intersect with the fertility of the soil, and the aspect of the hills? Is there a preference for one kind of landscape rather than another? If we imagine people stood 1.8 m tall, and there’s no vegetation in the way, what might they have been able to see?

Burials at Linlithgow (Python)

Dr. Rachel Optiz is a digital archaeologist and landscape archaeologist at the University of Glasgow. She has made a series of computational notebooks for her Archaeology of Scotland class exploring some of the ways we might query spatial data and maps in the Python programming language. Right-click on the link below to launch her binder:

https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/ropitz/spatialarchaeology/master

And then select the linlithgow_spatial.ipynb file, and work through that. (Remember, you select the first cell in the document, then hit run. Wait for it to finish - it’ll have an * in it when running, replacing with a sequential number when finished). This notebook explores looking at spatial relationships at a small scale - within a group of Medieval burials from the Carmelite Monastery at Linlithgow.

You might get an error towards the end to the effect that something called descartes is not installed. To fix this, click the + to create a new cell. Then, put the following code in the cell:

!pip install descartes

and then hit the run button.

It is possible to just continue without correcting that one particular error.

But now, let’s turn to a bit larger scale. While the previous work was done in the Python language, this next one will use R.

Exploring a landscape (R).

Daniel Contreras has a chapter in Ben Marwick’s online book, ‘How To do Archaeological Science in R’ about using R as a GIS. We’re going to follow along with that chapter, but I have modified the code slightly so that it will run in a virtual computer in your browser, using the coding environment R Studio and the language R.

-

Launch a virtual computer running RStudio in your browser by right-clicking on this link

-

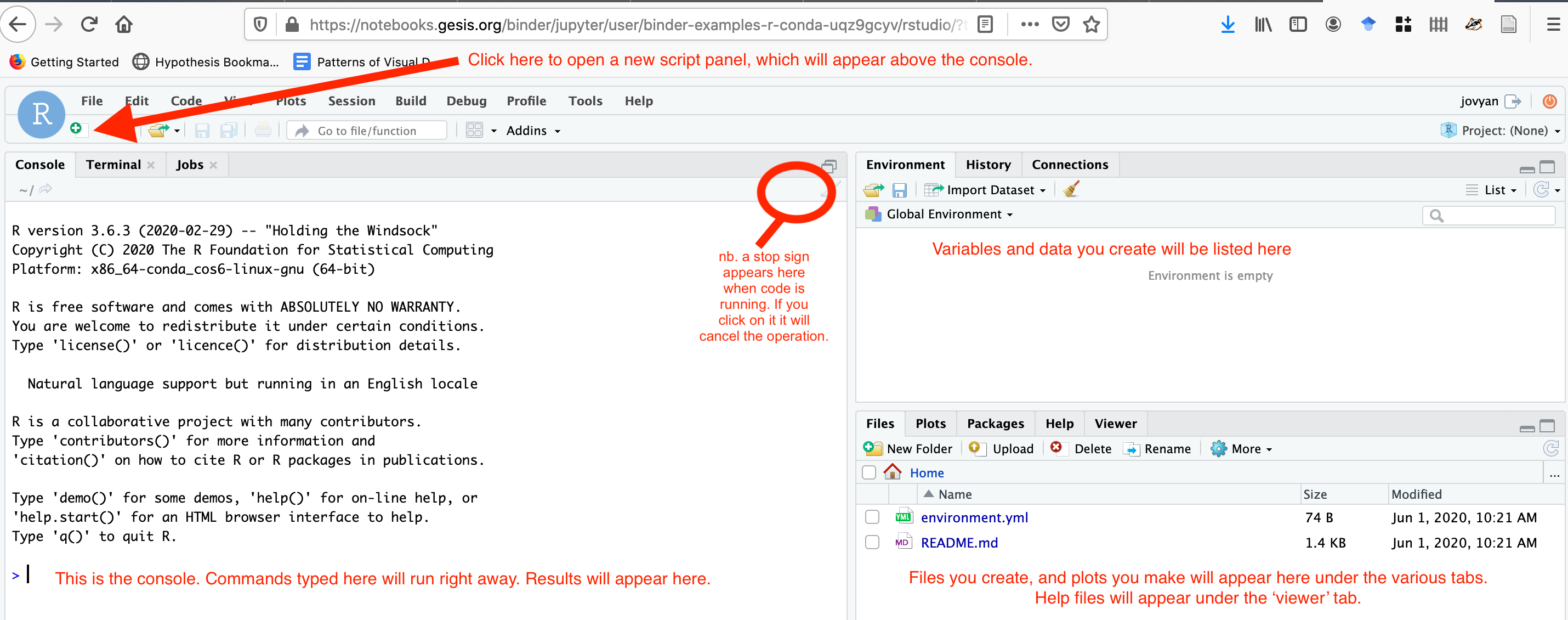

The interface for RStudio looks like this:

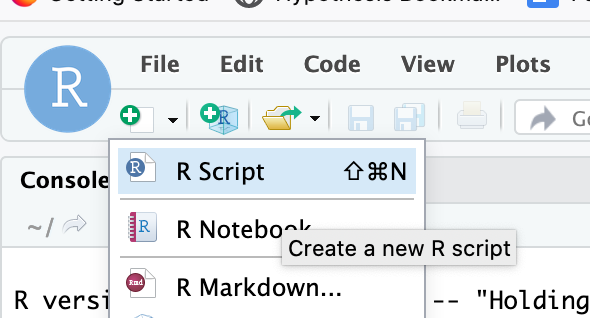

- Create a new script:

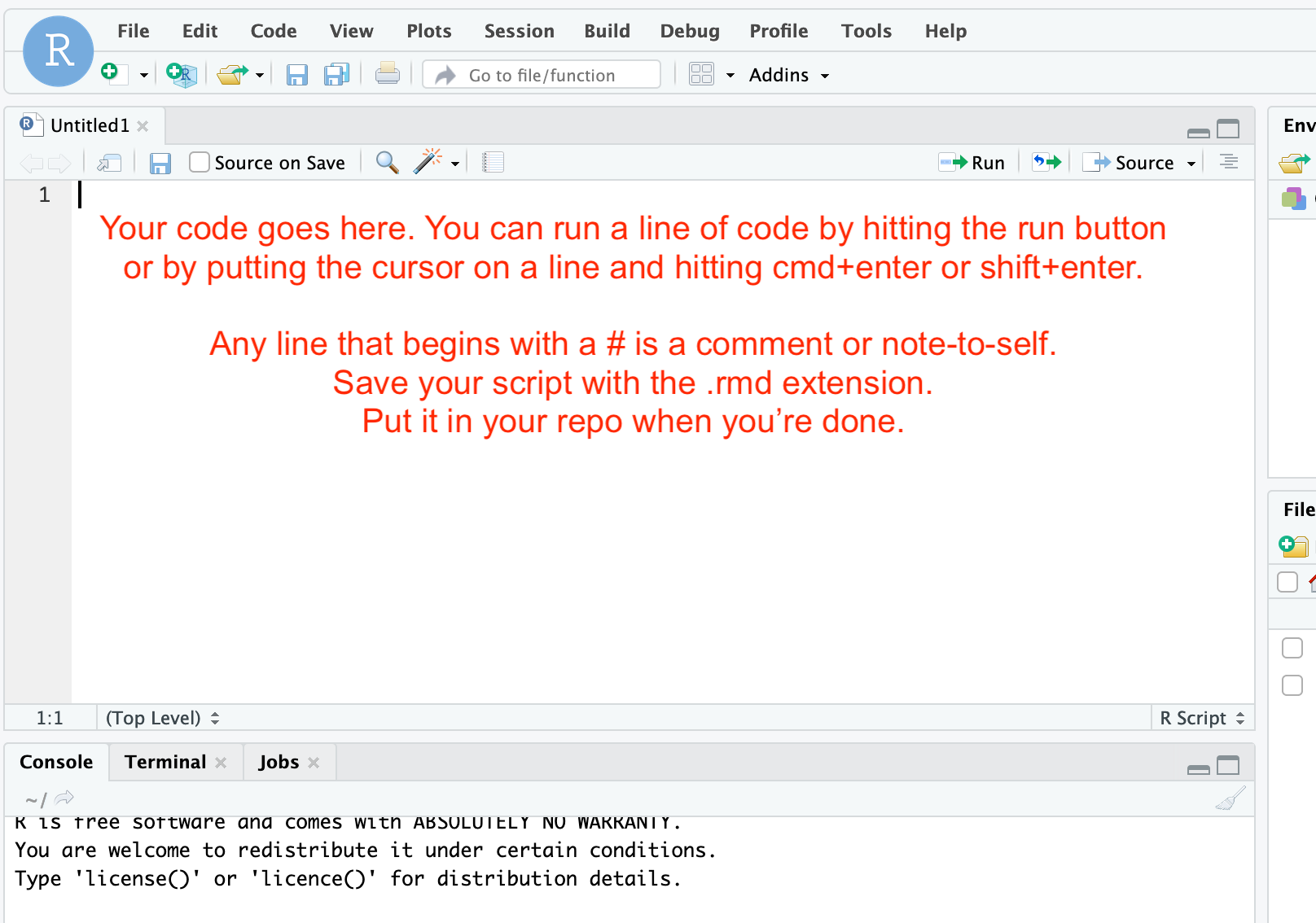

- The

dem-gis.Rscript that you want can be found at this link. Right-click and ‘save-as’ that file. Use your text editor to open it, then highlight and copy all of the text. In the version of R Studio that is open in your browser, paste the text in the script panel in R Studio.

Now you can run the script. Put the cursor at the top of the file at the start of the line. You can then run each line by hitting the ‘run’ button, or by using the keyboard shortcut (cmd+enter or shift+enter). Read the comments (which are marked with a # sign) and follow all instructions.

Work your way through Contreras’ tutorial, using the dem-gis.R code.

Now, the advantages to using R or Python to do this kind of work lies in the idea of reproducibility. You can see every step in the reshaping of the data, in the filtering and layering.

Many archaeologists use the open source QGIS program to work with their data, which provides a visual graphical user interface. It’s a very powerful piece of software, and does allow scripting and other interactions. The problem with software-via-a-GUI is that it becomes very hard to reproduce exactly the sequences of clicks and so on that a person uses. Nevertheless, if mapping intrigues you, you should play with it. An excellent guide, ‘QGIS for Archaeologists - Getting Started’ in the BAJR Practical Guide Series by Jake Streatfeild-James (2016) is at http://www.bajr.org/BAJRGuides/42_QGIS_StarterGuide/42_BAJR_Guide_QGIS.pdf. (By the way, many archaeologists use commercial projects from Esri to handle their spatial data; if you find data files ending with .shp, a ‘shape file’, that’s an Esri readable format and indeed, the industry standard.)

If you really want to get into QGIS, then QGIS4Arch is for you, a series of videos by Ed Gonzalez-Tennant.