Introduction

I wanted you to have some experience of collecting data, and of how data models (or our expectations of what we’ll find) influence the subsequent work that we can do with the information that we collect. ‘Data’ means things given but the goal (a goal) of this exercise is to see this information more like ‘capta’ or things created/crafted/captured.

Archaeology has some well established models for capturing the observations made at the trowel’s edge. In the UK for instance (where I did most of my archaeological training) the ‘single context’ recording system as developed by the Museum of London Archaeology Service is more or less used (with variations) everywhere. (Here’s the manual).

We clearly can’t dig anything, in this time of Covid (and besides, it takes time to obtain a license to excavate in Ontario; looking at monuments in cemeteries however doesn’t fall under the rubric of the archaeological licensing scheme). We will be looking at archaeological data collected by others (from places like the Archaeological Data Service), but it seemed to me that you should experience just how much variability, reflexivity, and creativity is involved in trying to systematically collect information. Morgan and Eddisford argue (2019) that

the introduction of single context recording not only had a dramatic impact on the way in which archaeology was undertaken, but also revolutionized the way social relations on site were structured. Single context recording promotes individual empowerment of diggers, allowing them to contribute to collective knowledge construction on site. Equally, it promoted a more horizontal management structure.

In a way, the scheme that we are going to use (adapted from ‘Discovering England’s Burial Spaces’ is similar to what Morgan and Eddisford say about single context recording: one grave at a time, you (plural) build up a broader picture of what is going on. But recognize this too: how we record data has an impact not just on the past, but the present (see also Perry 2018, 217)

Mortuary Archaeology

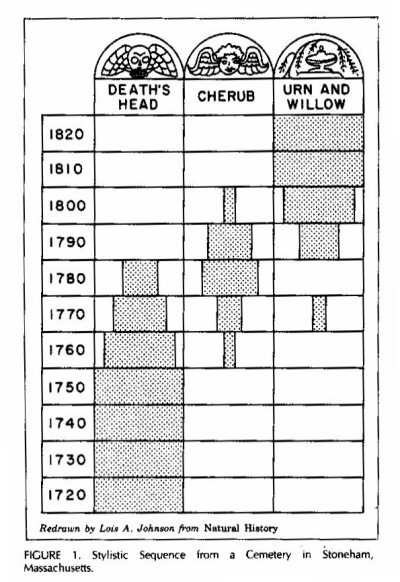

The study of graveyards is one point where history and archaeology intersect, as both disciplines have their own bodies of literature connected with exploring how humans have dealt with their dead. I remember being taught as an undergrad the concept of seriation with reference to motifs on New England headstones (‘Death’s Head, Cherub, Urn and Willow’ by Deetz and Dethlefsen.)

The count of headstones with different motifs, when organized according to date of death, demonstrates how fashions evolve even within gravestone motifs. Which also means you can use a motif to suggest a likely date for a stone…

Now, mortuary archaeology as a branch of bioarchaeology has tended to focus more on the human remains (an overview by Bettina Arnold and Robert Jeske is available here).

In my own research (The Bone Trade Project) I am looking at how and why people buy human remains (which they do these days over Facebook and Instagram) using computer vision and machine learning (artificial intelligence). Many of the people whose remains are now being traded were stolen from their graves; many never even made it to the grave (people who died homeless, for instance, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, could be claimed by schools of anatomy for dissection).

Ontario has a history of grave robbing as well - I found this notice in the Shawville Equity:

“Dr. Eberson, a dentist well known through-out the Ottawa Valley, was found drowned in the Rideau Lake near Portland recently, and his body was interred in the cemetary at that place. A few days since it was found that the body had been stolen by human ghouls. The coffin was kicked in and badly damaged by the graverobbers… No trace of the body has yet been discovered. “ – Shawville Equity, October 9 1890

Katie Daubs, writing in the Toronto Star, has a long piece on the history of grave robbing in Ontario.

A project looking at graveyards and gravestones therefore sets us up to talk about digital archaeology in a number of powerful and compelling ways.

When Archaeology Is In The Headlines

We can’t be discussing ‘mortuary archaeology’ without thinking of the unmarked graves at the government sanctioned, church-run residential schools; these schools were deliberately designed to forcibly assimilated Indigenous children into settler society (TRC of Canada 2015). The deaths, graveyards, and unmarked burials were never a secret; there was plenty of witness’ testimony. But over the last few months, archaeological approaches using ground-penetrating radar confirmed the location of graves at Kamloops and Cowessess amongst other locations; other Nations are now searching for the graves of their children.

Did your elementary school have a graveyard beside the play-yard? Mine didn’t.

Dr. Kisha Supernant, who directs the Institute for Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology (IPIA) at the University of Alberta, has been a leading voice on the need for ethical and trained archaeological GPR work to help communities who wish it. That’s a key point: the archaeologists do have training, tools, and techniques, but they must be invited.

But…

Deeply concerned about some of the stories I’m hearing about large companies who use remote sensing approaching communities about scans around IRS sites. I encourage any Indigenous community who is receiving these request to reach out for free advice from @UofA_IPIA

. Kisha Supernant, via Twitter.

I will copy in full the statement from IPIA following the release of the full report on the former Kamloops Indian Residential School:

Today, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc has released information about the preliminary ground-penetrating radar investigation undertaken by Dr. Sarah Beaulieu around the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School. Dr. Beaulieu engaged with Knowledge Keepers and Cultural Monitors to perform a preliminary, exploratory survey of an area where the experiences and testimonies of survivors indicated the presence of graves. The ground-penetrating radar work was undertaken by an experienced expert using best practices for the application of ground-penetrating radar to find possible unmarked graves and identified 200 targets of interest in the area surveyed. These targets have many characteristics of grave shafts identified in other contexts and are strongly indicative of burial locations. Further investigation of these targets is warranted, as is additional survey of other areas of the grounds associated with the Kamloops Indian Residential School. Testimonies of survivors indicate other graves are likely to be found in other areas around the Kamloops IRS.

Survivors and Indigenous communities have been speaking the truth of their experiences in so-called “residential schools” and related institutions for decades; it should not have taken the use of scientific techniques for the necessary attention to be paid to the truth of what happened to the survivors and to the children who never came home.

As AFN National Chief RoseAnne Archibald states: “We have always known.”

It is essential that Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc and other Indigenous nations are provided with all the resources they need as they undertake further work to find the burial locations of their children and take the next steps they deem necessary, including calls for justice and accountability. We at the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology (IPIA) support the call of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc to release the Student Attendance Records and to provide additional immediate and long-term resources from the federal and provincial governments. As noted in the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc media release, access to experts is critical:

“This work requires significant resources that includes dedicated and qualified personnel to bring truth to light and peace to family members of the missing children. This is what drove Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc to reach out to the Canadian Archaeological Association and the Institute of Indigenous and Prairie Archeology. It is also why Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc are offering a free webinar next week on remote sensing and grave detection in partnership with them.”

At the IPIA, we recognize the important role archaeological techniques can play in supporting communities to locate where their missing children might be buried. We are Indigenous-led and recognized as a national and international leader in using various remote sensing technologies (including ground-penetrating radar and drone mounted sensors) in burial contexts across the prairie provinces. We invite communities to reach out to us should they need advice on how best to approach the surveys around their schools in the hopes we may provide additional information and help navigating these emotional contexts. We also invite federal and provincial governments to reach out to us about how to coordinate and ensure communities have access to reliable, independent expert advice around the application of remote sensing for grave detection. Our Director, Kisha Supernant (Métis) is Chair of the Unmarked Graves Working Group of the Canadian Archaeological Association, which is developing resources for Indigenous communities about best practices around the use of remote sensing to detect unmarked graves.

You can view the full webinar on the use of GPR to help locate unmarked burials by the Canadian Archaeological Association and the IPIA here; the slides and pdfs are also available to download. I encourage you to watch the full video…

And then reflect on the differences here, between graves that are unmarked, and marked; between the hidden, and the celebrated. And the role this implies for archaeology.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC of Canada)2015aCanada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 - Origins to 1939. In The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. McGill-Queens University Press, Montreal, Canada

Conclusion

It seemed to me that a project where we explored local graveyards would tie together many of the strands that I wanted this class to weave together: it would also demonstrate the necessarily political work that is archaeology. The information that you collect will be used later in the course for some statistical analysis, and for the eventual final outputs that we put together. The issues that all of this will raise, the techniques that you will be exposed to, the literature: all of these will help push you towards an ethical digital archaeology. Archaeologists should be activists too, says Allison Mickel and Kyle Olson.

When the day comes that you will work with other kinds of digital archaeological data, you will be able to revisit your notes and journals from this class and have a head start on whatever task it is you wish to do.