Introduction

Humans have made virtual worlds since time immemorial (see, for instance, Lascaux). Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli was a virtual world. Disney World is a virtual world. Online is a virtual world but it’s still the real world.

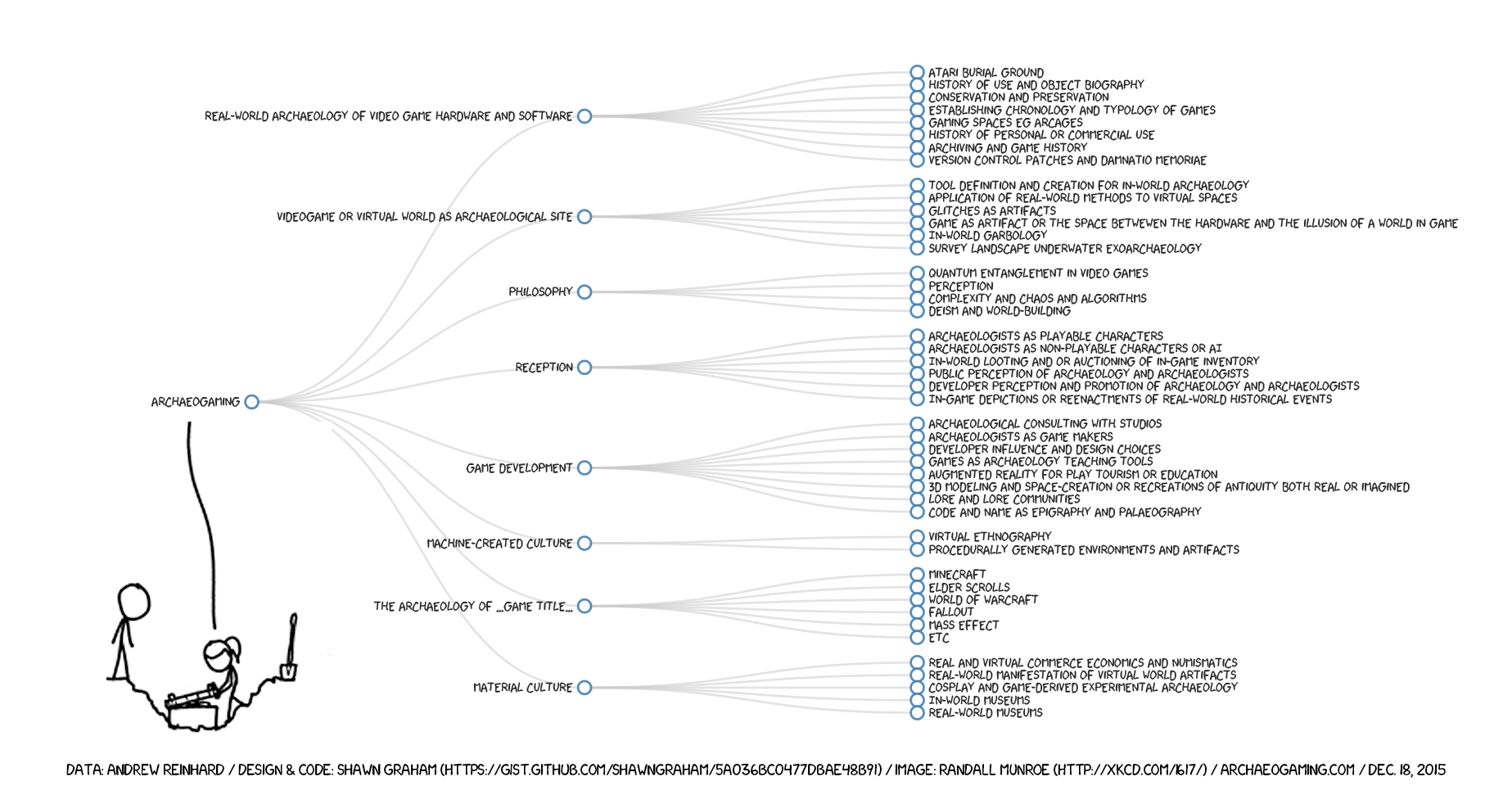

As this map put together by Andrew Reinhard and I suggests, there are a lot of dimensions to archaeogaming. I don’t know if it’s still on Netflix, but the ‘Atari: Game Over’ documentary is worth a look because it is a case of quite literal archaeology of video games.

Most of the time, no one excavates physical video games. But we do do work inside video games, and archaeologists do sometimes help design video games - Tara Copplestone, in ‘Designing and Developing a Playful Past in Video Games’ has written on the tension between good archaeology and good game design, and it’s well worth your time to read.

For my money, a video game does one thing really well: it teaches the player how to play it. If you’re really good at the game, you’ve internalized its representation of the world. And that’s why archaeologists need to think about storytelling, and ethics, and representation in video games. (More from me along this vein in this article.)

But there are other ways of approaching the worlds created in video games as archaeological spaces. This week, I’ll suggest four options.

Option 1: Graves and memorialization in-world

Here, I want you to select a game that you know well that includes within it graveyards or other memorials to the dead. Off the top of my head, I could imagine Dwarf Fortress, Dragon Age Inquisition, Witcher, or the Assassins’ Creed franchise. And then I want you to record gravestones and other monuments in the game, using our KoboToolBox recording system that we used for the Graveyard Project.

(This work is not without precedent; see the archaeological survey of worlds in the No Man’s Sky universe; there was even a code of ethics developed to guide that research.

But, but… games aren’t real worlds! What good would it be to study memorialization in there?

Virtual worlds are still human worlds, and the way death is memorialized in there might also provide us insight to how we construct death out here. Archaeology isn’t just about the past, remember. We spend a great deal of our waking hours in these virtual worlds. Perhaps studying memorialization in-world will give us insight into memorializations of the future? Perhaps it might tell us about how people form social relationships in-world? Let’s find out.

Go into the game, and take screenshots. Then, working from your screenshots, record them in our system. Think about, and record, the ways memorialization is constructed in these games, and how it is similar/different from the ‘real world’ data.

Option 2: Craft a ‘barely’ game

Rob MacDougall introduced me to the idea of ‘barely games’ years ago. With this option, I want you to devise a ‘barely game’ that could be played with our graveyards data.

This is for the entirely practical reason that designing and building games takes a lot of time and effort. Thus, your game might -

- be built in Twine; there are many tutorials on how to achieve different effects with Twine; you might start with the Twine Cookbook

- be built with Bitsy

- something else that you know of that I haven’t encountered. Key thing is: this has to be something achievable in a few days.

Option 3: Game Design Document

Another possibility is to sketch out a game design document for something a little bit more complex than a barely game, but certainly not as complex as a first person shooter. Maybe a deck builder? Something where the main gameplay maps onto the ways digital arcaheology looks at the world. (templates abound online; here’s one). I emphasize again: sketch. Focus on aesthetics and gameplay. Key element: it must use the information collected by this class.

Option 4: Investigate a Landscape

Go play Nothing Beside Remains. Map the site; try to understand the ruins by situating them in context with one another. Write/craft a research report of around 250-400 words.

Then, think about the kinds of literary tropes you depended on in order to write that report. You might want to think about this in terms of Section 3 from that article of mine. What does this imply for how ‘regular folks’ might understand - or be helped to understand - about archaeology?